The other half of the world: interview with someone living with hemianopia

Being affected by hemianopia means suddenly seeing the world in half. Not only in the most concrete sense of the term, but also in the perception of one’s abilities, autonomy, and future.

Behind the coldness of a neurological diagnosis lie deeply human experiences, made up of daily difficulties, adaptation, and the discovery of new strategies to continue living with dignity and independence.

In this exclusive interview, Marco (a fictional name used to protect his privacy) shares his journey. He talks about the first days after the neurological event and the beginning of neuro-visual rehabilitation. He also opens up about the challenges, fears, and small victories along the way.

It is not easy to describe what it means to live with hemianopia, especially if the diagnosis comes suddenly, at a time in life when nothing foreshadows such a profound change.

With honesty and courage, Marco chose to share what it means to live with a visual field deficit. Because facing such a life-changing condition takes real bravery.

Marco, when and how did you discover you had hemianopia?

I was 38 years old and had always enjoyed good general health and good eyesight: the classic “20/20 vision.” I was so unfamiliar with visual impairments that I thought the quality of vision was measured solely by the ability to see the classic letters from a distance.

I began to feel discomfort in daylight — being outside on a sunny day without sunglasses was torture. At the time, I was finishing my training to become a private pilot.

I flew light aircraft under VFR — that is, visual flight rules. In this type of flying, the pilot’s eyes are the primary instrument. I couldn’t keep the aircraft flying straight. To do that, you need to look ahead and fix your gaze on a point; it’s crucial to use peripheral vision to perceive the horizon line

I was always late in making corrections. This happened especially during landing, where quick maneuvers are required. You have to anticipate the aircraft’s movements to keep the runway steady in the windshield

I also started having trouble using the computer — the screen light bothered me. At first, I thought it was due to the new monitors. Then I realized the problem was bigger. Colors started appearing blue and purple.

I couldn’t understand the brightness of objects. I couldn’t tell whether something had its own light, like an indicator lamp, or was just a red dot on the screen.

The symptoms kept getting worse and were hard to describe — especially for someone like me, who had, until then, been completely unfamiliar with the world of visual impairments.

In fact, I hadn’t yet realized that I also had hemianopia.

I hadn’t noticed that my visual field had “narrowed“.

I thought vision was just a matter of “seeing or not seeing”, so I compensated with what I later discovered was the AHP (Anomalous Head Posture).

Even when driving, for overtaking or maneuvers, I often had to move my head. This habit can lead to motion sickness: a feeling of nausea, dizziness, or discomfort common in dynamic environments, especially in airplanes.

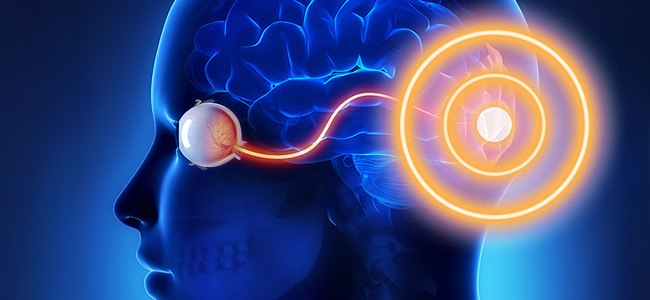

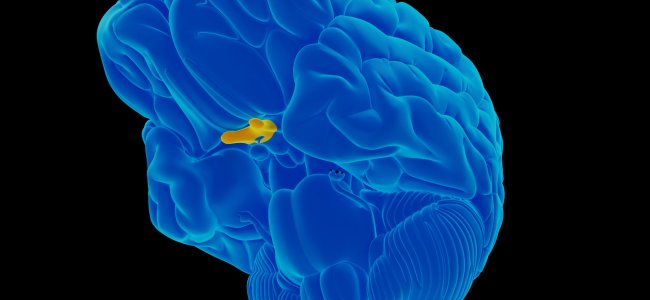

To clarify my answers in the following questions, I suffered from secondary hemianopia caused by compression of the optic chiasm. The compression was due to a craniopharyngioma at the pituitary stalk, a rare benign brain tumor that forms near the pituitary gland, which regulates many hormones.

My condition was almost completely resolved through surgery and neuro-visual rehabilitation exercises.

Besides the hemianopia, what I saw was similar to what happens when we press our eyes with our hands. After a moment, everything appears distorted. There are flashes and unnatural colors. This effect fades after a few seconds. In my case, that distortion had become part of my daily life.

How did you feel when you first received the diagnosis?

After an eye exam described as “within normal limits with slight visual field alterations”, I was advised to see a neurologist. That exam also came back negative. As a precaution, an MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) was requested — fortunately carried out very quickly by a highly experienced radiologic technologist (RT), who, noticing during the scan that something wasn’t right, performed multiple additional projections. Thanks to his initiative, the exam was reported just a few hours later.

After receiving a call asking me to collect the report, I brought it to my general practitioner. Without mincing words, he convinced me to go straight to the emergency room at Careggi Hospital (Florence), the closest one with a neurosurgery department.

Soon after, around the exam bed, I saw several specialists gather: neurologists, endocrinologists. They told me there was a “swollen gland“. Internally, I thought, “Well, it’s probably something that can be managed with a few medications at home”. Aside from the visual symptoms, I had no pain or neurological problems.

But that wasn’t the case. Shortly afterward, I was admitted to the neurosurgery department to undergo surgery for a pituitary craniopharyngioma that was compressing the optic chiasm. The surgery would be performed through the nose (via a transnasal-transsphenoidal approach), and the neurosurgeons reassured me that this type of access would help with recovery.

I state that, at the time, I had no idea what the pituitary gland was. Now I know that it sits at the base of the brain, behind the nose. It’s about the size of a chickpea and controls the body’s entire endocrine system, including the thyroid, adrenal glands, and testicles.

Can you share how you came to better understand your condition over time?

I was supported by the love of my family — and by my own ignorance. I only realized after the surgery that it had been a brain tumor. It was benign, but its behavior was unpredictable.

I remember an incredible moment: at night, lying alone in my hospital bed. In the silence of the ward, I opened my eyes after the surgery.

There was a large tree outside the window. I had been in the hospital for a couple of days, but I didn’t know what kind of tree it was, I could only see it as a green mass.

But, when I opened my eyes again in that same bed, in the moonlit night with light from the streetlamps, I clearly saw that it was a pine tree — its green needles glowing even in the dim night light, and I could see them clearly.

I could see colors again! I looked up and saw a TV mounted on the wall. It was off, but had a small red sticker on it, and I saw red! I saw it wasn’t a red light, it was just a red sticker.

I spent the entire night, still under the effects of the sedation, admiring the spectacle of “high-definition” vision and the sunrise outside the window.

How did healthcare professionals support you throughout your journey?

Their role was obviously essential, although at first I noticed a significant disconnect between ophthalmologists and neurologists. It was also difficult, in the beginning, to describe the visual disturbance, which was often labeled as “‘unspecified and of unclear nature”.

Do you feel the diagnosis of hemianopia was made accurately and in a timely manner?

It was neither timely nor accurate. The main issue I encountered is that, unlike an imaging exam where the patient remains passive, hemianopia is diagnosed essentially through a visual field test, in which the patient plays an active role.

Having never done one before, the first times I certainly didn’t perform it correctly, which skewed the results.

Did you receive helpful advice and ongoing support?

At first, no: effective treatment only started after the MRI. Unfortunately, this is a “rare condition” with unusual symptoms, so the doctors initially relied on empirical therapies before they could precisely define the situation.

Through my journey, I realized how important it is for the patient to recognize their condition and describe it with clear medical terms every time they see a specialist.

You need to be detailed, but not overly long. It’s also helpful to provide a scale of improvement or worsening compared to other reference points.

Did they suggest any visual rehab or other types of rehabilitation to you?

Only once, while I was repeating the visual field test before the surgery, I exchanged a few words with an orthoptist.

I remember that, having limited eye mobility and sitting lower than her at the visual field machine, so I couldn’t see her face, I read “ORTHOPTIST” on her uniform and asked her what her job involved. She briefly explained and told me I would definitely need neuro-visual rehabilitation from that kind of specialist after the surgery.

I forgot about that conversation, overwhelmed by all the other visits and a subsequent hospitalization, until a friend pointed out my strabismus, which I hadn’t noticed before.

That’s when I remembered her and looked for an online consultation. I found a pair of orthoptist professionals from Sicily who agreed to conduct remote visual rehabilitation sessions. These turned out to be quite effective, using a webcam and self-produced graphic materials.

After all, I wouldn’t have had the time or consistency to go to a clinic.

I discovered that the brain is a wonderful machine, capable of adapting and finding solutions sometimes without even realizing it. Paradoxically, I only understood what I had lost when I began to regain it after the surgery and thanks to the orthoptic exercises.

What strategies do you use to compensate for the loss of your visual field?

I move my head (an abnormal head posture) and rely more on touch, almost unconsciously because the condition developed gradually. Using touch has remained with me even today: I realize I do some things without looking. For example, plugging a cord into a socket in a corner, I believe it’s useless to try to look there, even though nowadays, if I did look, I would see well and take less time.

How do you deal with safety concerns due to your limited vision?

Fortunately, I have regained a satisfactory visual field, although a small area remains missing at the bottom. Practically, when I’m standing and move my hands around waist level, I can’t perceive the movement. Currently, I don’t encounter situations where I feel there are particular risks.

How have your family, friends, and colleagues reacted and supported you?

Besides their affection and closeness, they anticipated the objects I needed in the hospital — from fresh juices to small items like slippers suitable for the shower, and so on.

They did this without me having to ask, as I was suddenly thrown into a situation very different from my previous way of life.

How do you maintain a positive and resilient mindset every day?

I loved the life I had before and wanted to get back to it as soon as possible. I realized that, despite everything, with the right mix of luck and “practice”, this condition is manageable.

Taking medication doesn’t bother me much either, since in a way it helps me regain a quality of life I had lost years ago or perhaps never truly had (considering the hormonal imbalance).

What advice would you give to someone facing hemianopia?

Describe your symptoms clearly, use the appropriate medical terms, and report them accurately.

You need to understand that vision is not just “seeing or not seeing”, but how you see. Try to establish fixed reference points. For example, sit in a specific spot in the room and look at an object without moving your head, then track any improvements day by day. Finally, report everything to your healthcare professional.

Those who care for us are not “inside the patient’s mind” and need precise data and references to effectively monitor the ongoing therapy.”

What improvements would you like to see in the healthcare and social systems for people living with hemianopia?

I believe neuro-visual rehabilitation should be considered just as essential as motor rehabilitation. It’s important to raise awareness among patients and their families that this is an exact science, not some improvised or secondary support.

I would also like to sensitize healthcare authorities about its importance, as it can sometimes be the difference between disability — with its social costs — and a normal, socially active life.

Would you like to share anything else about your experience?

Yes, my condition not only did not show up in the first visual field test, nor in the Ishihara plates (those with numbers inside colored dot circles), but it mainly manifested as a slowed ideation and a difficult-to-explain slowdown in vision.

For example, a person with normal vision walking on a sidewalk is able to recognize “out of the corner of their eye” and in a fraction of a second whether the person approaching them is a young or elderly individual, perhaps someone known. In my case, this operation took 5-6 seconds.

Moreover, some acquaintances, curious about my orthoptic exercises, asked me to explain and demonstrate them. When asking them to repeat the exercises, I noticed that several people had significant difficulties with fixation, eye movement, and tracking exercises.

The feeling is that visual disorders are actually much more widespread than is commonly thought and are probably a cause of unmonitored accidents and injuries.

Consider, for example, a person with hemianopia who drives a car or operates machinery in coordination with other colleagues.

When vision changes, everything changes

This story reminds us that behind every diagnosis there is a person—with dreams, fears, obstacles, and daily battles. Hemianopia is not just a clinical term: it is a reality that changes the way we see the world, in the deepest sense of the word.

Yet, as Marco has shown us, even when vision breaks, life can find its balance again. A balance made of adaptations, new habits, but also hope, affection, and conscious choices.

Thanks to experiences like this, we can build greater understanding, raise awareness among those who still underestimate the impact of these disorders, and strengthen the delicate bond that connects caregivers and those who live daily with a neurological condition.

Today, thanks to neuro-visual rehabilitation, even remotely, there are targeted pathways that can concretely improve quality of life.

Getting informed and seeking a specialist can make the difference between merely living with a visual deficit and actively facing it, equipped with clear and realistic tools and goals.

To those currently facing hemianopia, we want to say: you are not alone. Every story like this is an invitation never to give up on the half that’s missing, but to value every fragment that remains.

You are free to reproduce this article but you must cite: emianopsia.com, title and link.

You may not use the material for commercial purposes or modify the article to create derivative works.

Read the full Creative Commons license terms at this page.