Neglect: Rehabilitation perspectives and intervention modalities

Neglect, or spatial neglect syndrome, is among the most investigated disorders in neurorehabilitation because of its peculiar symptoms and its impact on the daily life of the affected person.

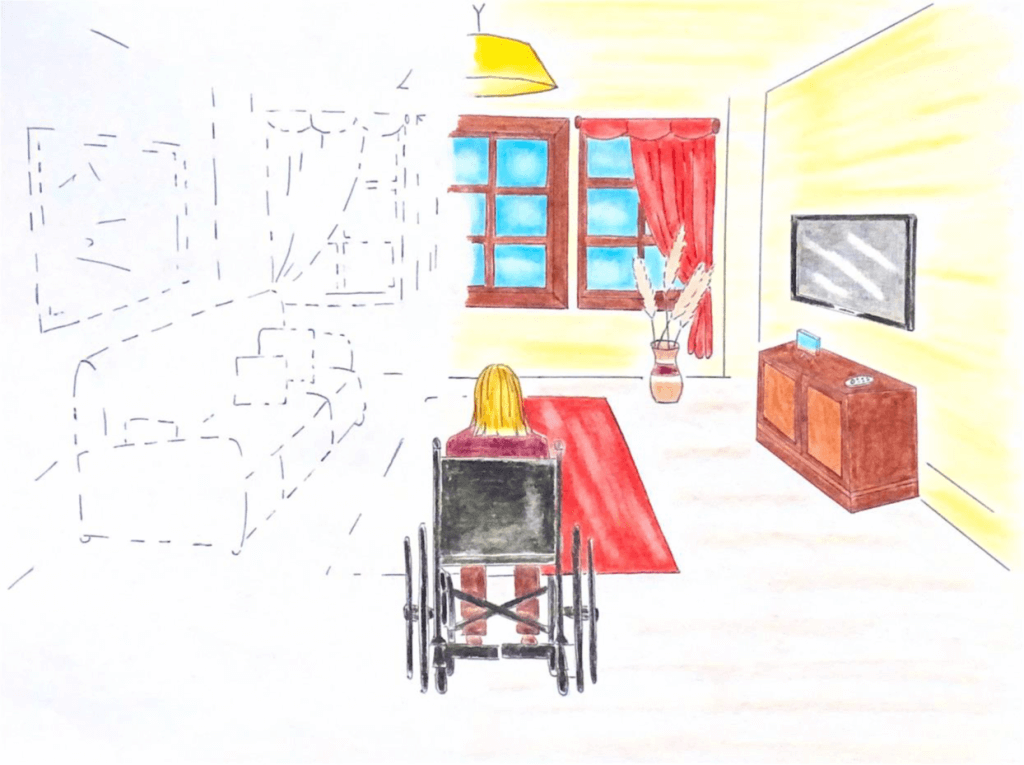

This clinical condition leads the person to disregard a narrow part of space, usually on the left, thus finding themselves performing activities of daily living asymmetrically. Such as, for example, eating, shaving or applying makeup while considering only the left side of the plate or of one’s body.

Sometimes, people complain that their food portions are too small, when in fact it is because they eat only the right side of the plate, ignoring the food on the left side of the plate (fig. 1).

Fondazione Santa Lucia IRCCS, Rome.”

Altered of Personal and Peripersonal Space

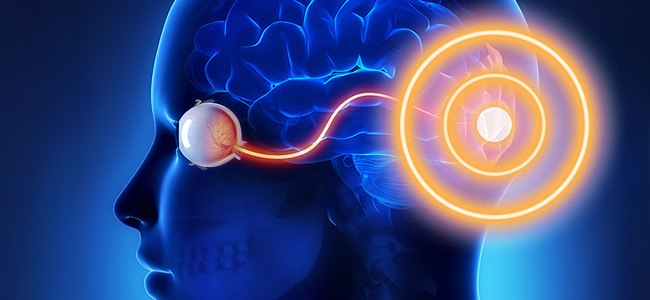

But how is it possible to unknowingly ignore a part of one’s body or space?

Neglect is an acquired neurocognitive disorder that impairs people’s ability to interact with stimuli of various types from the left hemisphere, that is, the one contralateral to the lesion. The latter tends to be a brain insult that affects the right hemisphere and impairs the ability to explore what is present or what is occurring in the contralesional space, i.e., the left one. This can occur even in the absence of a motor or visual deficit that prevents one from directing attention to that part of space.

Depending on the severity of the disorder, the deficit may also affect mental representational capacity, such as mental images of a clock or a city square.

The patient with spatial emineglect, therefore, acts as if everything to his left does not exist, with an altered perception of both the space around him and his own body. In addition, people with neglect are not always aware of their exploration difficulties because the condition is often associated with anosognosia, that is, lack of disease awareness. This aspect complicates the clinical picture and the recovery of the deficit, posing an important barrier in the rehabilitative care of the patient.

The rehabilitative procedures of Neglect

Given the complexity of the disorder, a multidisciplinary team consisting of professionals such as neurologists, orthoptists, physical therapists, and neuropsychologists is necessary. The skills of the rehabilitation team are basic to identify and treat the symptomatology, through rehabilitation programs tailored to the specific needs of the person. Rehabilitation of spatial eminegligence is implemented with different methodologies depending on the main component of the disorder and the influence of the pathology on the psychological sphere.

Among the various therapeutic approaches, neuropsychology proposes top-down and bottom-up rehabilitation approaches that exploit brain mechanisms to reduce the imbalance and conflict present between spaces and spatial representations.

Top-down mechanisms

Rehabilitative procedures that rely on top-down mechanisms require the patient to actively orient toward the neglected field, with the aim of directing attention to the part of space where stimuli are usually omitted. They typically include a series of visuospatial exercises with different levels of difficulty and characteristics.

A practical example are visual-spatial scanning trainings in which a series of different stimuli are presented on a screen in various spatial positions, requiring the patient to locate them. Treatments are adapted to the patient’s needs by varying aspects such as the time of stimulus appearance or the time interval between stimuli.

Many types of treatments are also usable with paper-and-pencil tasks: for example, the patient is asked to cross out all the stimuli he or she sees on a sheet of paper, scanning it from left to right and trying to omit as few as possible. In addition to visual detention tasks, exercises in reading, copying sentences, copying drawings and describing figures can also be used.

Many types of treatments are also usable with paper-and-pencil tasks: for example, the patient is asked to cross out all the stimuli he or she sees on a sheet of paper, scanning it from left to right and trying to omit as few as possible. In addition to visual detention tasks, exercises in reading, copying sentences, copying drawings and describing figures can also be used.

To optimize performance, we make use of visual or auditory cues, such as red bands at the extremes of space or sounds coming from the left hemispace. Top-down trainings are widely used, especially with acute patients, because they are intuitive and easy to apply. However, despite the substantial literature behind them on their effectiveness, since they are based on the ability to voluntarily control attention there are cases where they cannot be applied because of the patient’s limitations or deficits.

Bottom-up mechanisms

Rehabilitation procedures that follow a bottom-up approach do not require active patient participation but, promote implicit orientation to the neglected field through passive and/or active proprioceptive stimulations. External stimulations, such as sensory, optokinetic or proprioceptive stimulations, can be used to increase the patient’s interaction with the neglected contralesional space.

In this setting, there is an increasing use of rehabilitation protocols that require pointing (pointing) exercises to be performed while wearing prismatic or prism lens goggles. These glasses are designed to deviate the visual field 10° to the right and induce a visual adaptation termed, precisely, prismatic. The prismatic adaptation achieved by the training modulates brain activity, exploiting motor sensory mechanisms and visual attention to compensate for the patient’s deficit.

The benefits of rehabilitation training

In order to be effective, rehabilitative trainings must be performed with intensity, frequency and duration over time. In fact, with daily practice it is possible to achieve benefits not only in visual exploration but also at the level of spatial representations.

In addition to that, since neglect is characterized by a set of deficits related to the impairment of conscious information processing, during the rehabilitative intake of the patient with neglect, it is essential to work in parallel not only on the deficit but also on the awareness of its effects and pathology.

Therefore, rehabilitative treatments work mainly on developing awareness of the deficit and learning strategies to compensate for neglect through exploratory coaching and observation of the difficulties that emerge. Thus, although there is a gradient of spontaneous recovery in neglect, intervening early with validated protocols leads to improvements that are stable over time and that generalize to all aspects of the person’s life, facilitating them.

Bibliography

- Facchin, A., Toraldo, A., & Daini, R. (2012). L’adattamento prismatico nella riabilitazione della negligenza spaziale unilaterale: Una rassegna critica. MR Italian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 26(3), 33-40.

- Felten, D. L., & Maida, M. S. (2017, March). Atlante di neuroscienze di Netter. Edra.

- Frassinetti, F., & Ladavas, E. (2006). La riabilitazione del neglect attraverso diversi tipi di stimolazione sensoriale e l’adattamento prismatico. In La riabilitazione neuropsicologica. Premesse teoriche e applicazioni cliniche (pp. 325-342). Masson.

- Guida per i familiari della persona con Neglect, Fondazione Santa Lucia IRCCS, Roma.

- G. Vallar and C. Papagno, Manuale di neuropsicologia, Terza ed. Bologna: il Mulino, 2018.

- Kandel, E., Schwartz, J., Steven, T. M., Siegelbaum, A., & Hudspeth, A. J. (2014). Principi di neuroscienze (IV). Milano: Casa Editrice Ambrosiana.

- Làdavas, E. (2012). La riabilitazione neuropsicologica. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Làdavas, E., & Berti, A. (2014). Neuropsicologia. Bologna: Il mulino.

- Làdavas, E., Serino, A., Bottini, G., Beschin, N., & Magnotti, L. (2012). Riabilitazione dell’eminattenzione spaziale unilaterale o neglect. La riabilitazione neuropsicologica: Un’analisi basata sul metodo evidence-based medicine, 35-56.

- LIVOTI, V. Potenzialità e limiti dell’uso dei prismi ottici nella riabilitazione del neglect.

- PRISMA – Bollettino Di Aggiornamento Dell’associazione Italiana Ortottisti Assistenti In Oftalmologia. Spedisce: Centro Organizzazione e Congressi, via Miss Mabel Hill 9, 98039, Taormina, Anno 2013, Numero 2

- Rusconi, M. L., & Carelli, L. (2011). Efficacia a lungo termine della riabilitazione della negligenza spaziale unilaterale mediante lenti prismatiche: uno studio preliminare. QUADERNI DEL DOTTORATO IN PSICOLOGIA CLINICA, 2, 13-40.

You are free to reproduce this article but you must cite: emianopsia.com, title and link.

You may not use the material for commercial purposes or modify the article to create derivative works.

Read the full Creative Commons license terms at this page.